No one truth: Pentridge Prison Tours

Pentridge Prison Tours

Melbourne, Australia

Art Processors led the creative transformation of Pentridge Prison, opening up this famous historical site as a new destination for locals and visitors with powerful storytelling through interpretive design and cinematic audio.

Pentridge was anything but a blank canvas. Despite extensive urban renewal, the remaining cell blocks retain a deeply foreboding atmosphere and working with such a historically-charged site presented our team with unique challenges and opportunities. The tours we designed don’t shy away from the frequently dark history of the place. Rather, we ask visitors to embrace the discomfort, complexity and ambiguity of the stories, and consider for themselves the nature of justice and punishment in our society.

Art Processors have been fantastic and instrumental in bringing these powerful stories to life in their rawest, most truthful form. They have managed to intertwine evocative and emotional audio experiences with moments of silence to highlight the gravitas and significance of each inmate’s personal narrative. The National Trust, Victoria believes that for too long, these stories have been shrouded in mystery and although the past is confronting, it is crucial that we do not forget the realities of those who were incarcerated, and we respectfully learn and share their truths.

– Simon Ambrose, National Trust (Victoria) CEO

Inside the bluestone walls

Immersive audio tours lead visitors through the site’s history, from its original and continuing identity as Wurundjeri Land to the bluestone walls of Pentridge Prison and its closure in 1997. From time spent inside by some of Australia’s most notorious criminals to the anecdotes and experiences of thousands of people over several generations, the tours are a multifaceted exploration of the prison’s history.

Once the headphones are on, there’s no further need to interact with the device—as you explore the site, the device plays a narrative corresponding to the theme of that space, connecting visitors with the lived experience of those who spent time there. We interviewed former inmates, their families, correctional officers and others connected with the prison to develop the tours. Collaboration with the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation was crucial and their insights gave a critical perspective on First Nations people and the prison system. Seeking to address this issue with raw honesty—but also sensitivity for those who experienced, and continue to experience, the trauma of systemic failure—added another degree of complexity to an already difficult thematic landscape.

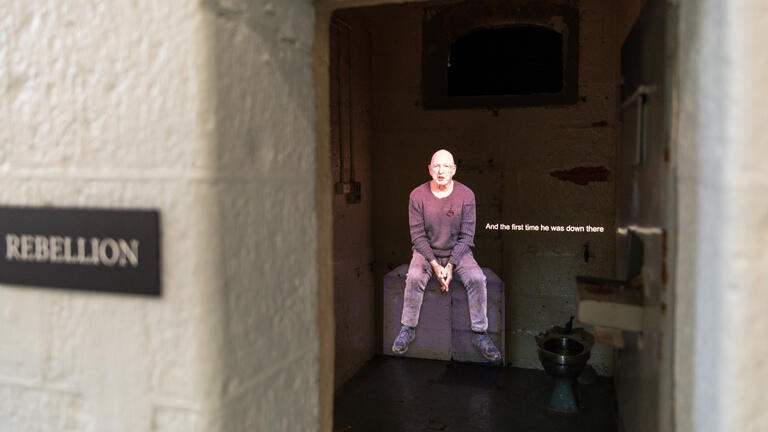

Our award-winning installation design heightens the experience. Various cells faithfully recreate prisoners’ austere living conditions, while others feature inmates as lifesize video projections giving first-person narration. Collections of historically significant artefacts are exhibited alongside collages of historical documents, photos and other graphics, while other cells are preserved as closely as possible to their original condition so visitors can experience them authentically.

This project brought together our end-to-end capabilities in exhibition design, location-aware audio and creative technology, built upon a foundation of rigorous research and nuanced storytelling, to create a heritage experience like no other.

I'm not a particularly ghoulish person - I don't like ghost stories, I'm not a fan of true crime. But new tours into Pentridge Prison, in Melbourne's inner north, tell stories of repentance and revenge, of rehabilitation, rebellion and regret. And that I find totally compelling. Toward the end of my tour, I find myself alone in a cell entitled Last Days, where inmates waited for their execution. A red light flashes in the cell and I jump back, to see the flicker of a man in the cell behind me. It's only a life-sized video, but my heart has stopped. The audio tour concludes, ‘Thank you for doing time here today.’ I'm so glad I never did.

– Belinda Jackson, Beyond the bluestone walls: Tour Melbourne's Pentridge Prison, Escape Travel, April 21 2023